The Bane and Backbone of Economic History

|

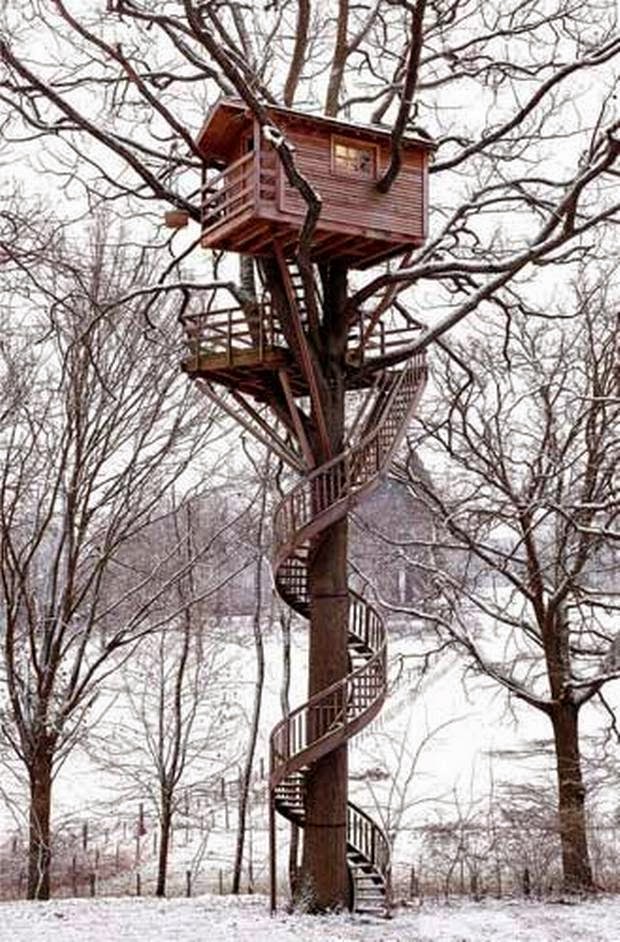

| Creatively adaptive Property Rights stand tall in the English woods |

Property rights are legal appropriations of ownership, use, or disposal of factors of production and consumption: land, labour, technologies, or capital. Self-evidently, the establishment of secure property rights -- identifiable, predictable, enforceable, enduring rights of private ownership and usage over anything that can be exchanged in the market -- is a precondition of modern market-based economic growth.

In a market economy it must be possible to appropriate and have free disposal of the non-human materials of production. Expansion of property rights expands the scope for improving market freedom and profit-making by creating rational expectations or calculable certainty that -- now and far into the future -- the entrepreneur can securely transfer wealth to the sphere of capital investment, and then rightfully appropriate advantages he or she gains from entering that investment for competition in the market.

In a market economy it must be possible to appropriate and have free disposal of the non-human materials of production. Expansion of property rights expands the scope for improving market freedom and profit-making by creating rational expectations or calculable certainty that -- now and far into the future -- the entrepreneur can securely transfer wealth to the sphere of capital investment, and then rightfully appropriate advantages he or she gains from entering that investment for competition in the market.

It has long been argued that England was quite different from the rest of Europe and the world because from a very early period (“time immemorial”) its people enjoyed relatively secure property rights in land ownership. 18th century French philosopher Charles Montesquieu concluded after reading Roman historian Tacitus that England’s “beautiful system” of laws for property and inheritance was copied from an ancient system invented in the woods of Germany, yet only the English woods retained and improved it. English lawyers from the 15th to 19th century argued also that the common law system of individual private property rights was uniquely conjoined to the economic and political-administrative system. In the 1970s historian Alan Macfarlane seriously irritated many fellow historians with a triumphant summary of his thorough analysis of literature and data on the socioeconomic impacts of land laws:

“The majority of ordinary people in England from at least the thirteenth century were rampant individualists, highly mobile both geographically and socially, economically rational, market-oriented and acquisitive, ego-centred in kinship and social life.”

However, if the legal system regulating land really was the backbone of England’s dynamism, the vertebrae of the system were continually thickened and conjoined in more complex patterns by economic change itself, which was driven in turn by international competition, changing social structure, political innovation, wars, and the countervailing pressure for new forms of property rights periodically adapted to changed environment. In other words, property rights aren't the only story, and their own story changes through time!

Think of the difference between the rudimentary legal guaranties needed for powers of control over plots of land as opposed to control over complex debt instruments or modern financial capital. Take the Glorious Revolution 1689 as a random point. The debates we examined in another post still reverberate today around a famous claim in 1989 that something had happened in 1689 to create, improve, or make credible and secure the property rights, which, intentionally or providentially, made financial markets feasible.

The Debate: ‘It ain’t so!’ exclaim some critics. Property rights in England were already well protected, insists a traditionalist. That’s irrelevant, retorts another, they were not a noticeable problem in the landlocked 1489 or 1589, but by 1689 they lacked the teeth for capitalism. What say ye then, cries another, to the fact that the strengthened post-1689 parliament meddled more than ever before with taxes, expropriations and eradications, which weakened property rights (in land) at precisely the time when economic growth (with secure finance) became airborne? Also, why on earth should a parliament comprised of landowners have striven to uphold property rights of a rising monied class holding government bonds? Change yer focus, shout the others, and then you’ll see why the important new rights in 18th century England were “public property rights” to tax, i.e. the innovations permitting government to sustainably pay its onerous debts to bondholders. To this the calm traditionalist replied (and this gentleman has the last word) that the flexibility and stability offered by English common law -- not property rights per se -- facilitated the key financial innovations.

Arguments like the ones above are the bane of the discipline of economic history. Intellectual property rights permitting, blogs like mine can fruitfully appropriate and profit from their surplus entertainment value. You would be a fool to surmise, however, that the argument is about the need for property rights. Most are agreed (deep down) that property rights are vital vertebrae of historically successful economies.

Of course, it is often correct to say [see the 'credible commitment' debate] that many factors other than property rights determined a particular sequence or combination of processes which in their totality gave England a comparative advantage over all other European countries, or else that property rights were more or less causally determinant in specific sectors or periods. Maybe Macfarlane can also plausibly claim that the legal infrastructure permitting solid power of control over property was the real thing that incentivised individualism, social mobility, rationality, and market enterprise in England.

We could discuss ad infinitum types of sequences in the appropriation of means of production, or types of appropriation, and the types which are positive or negative for the development of modern capitalism. In this post I will end with just one historical distinction, which anticipates and squashes (to pulp) a usual criticism of capitalist property.

Whenever the masterful pioneer Max Weber talked about appropriation of property rights he spoke simultaneously of their liberating effect on economies and also their potential to constrain economic freedom. There is always a chance that formal freedoms of contract and property, rather than equally empowering all who aspire to profit making, might only serve the interests of those who have economic power at the time when the laws to protect property are enacted.

"The result of contractual freedom is in the first place the opening of the opportunity to use, by the clever utilisation of property ownership in the market, these resources without legal restraints as a means for the achievement of power over others. The parties interested in power in the market thus are also interested in such a legal order. Their interest is served particularly [by] legal empowerment rules [that] create the framework for valid agreements which, under conditions of formal freedom, are officially available to all. Actually, however, they are accessible only to the owners of property and thus, in effect support their very autonomy and power positions."

Guaranties of property became formal rights because of the influence exerted by the most powerful existing property owners. Weber would nevertheless go on to explain in detail how and why the very same formal rights subsequently empowered all future owners of land and capital by giving every non-elite person more impersonal right and opportunity to usurp monopolistic appropriations through market competition. Before long the power of property was *less* than the power gained by intelligent mastery of impartial market conditions, market peace, and market legality.

A recent book deepens that insight with a cautionary paradox. Although property rights in land had become "very secure" for "most people" in England, "for the most powerful individuals, ownership and tenure in land remained subject to conflicts within the dominant coalition". In other words, powerful property owners do not necessarily get their way and hold sway. Why? - because they fight so much among themselves.

Progress in property rights was never settled or uni-directional. Property rights were the backbone of England's political economy, and yet they were successively a bane of every generation of economic and institutional actors. Hence they remain the centre of attention in economic history.

Progress in property rights was never settled or uni-directional. Property rights were the backbone of England's political economy, and yet they were successively a bane of every generation of economic and institutional actors. Hence they remain the centre of attention in economic history.

Michael G. Heller ©2014